(Author: Muskaan Bansal, pursuing BA LLB (Third year) from Guru nanak dev University, Regional Campus, Jalandhar.)

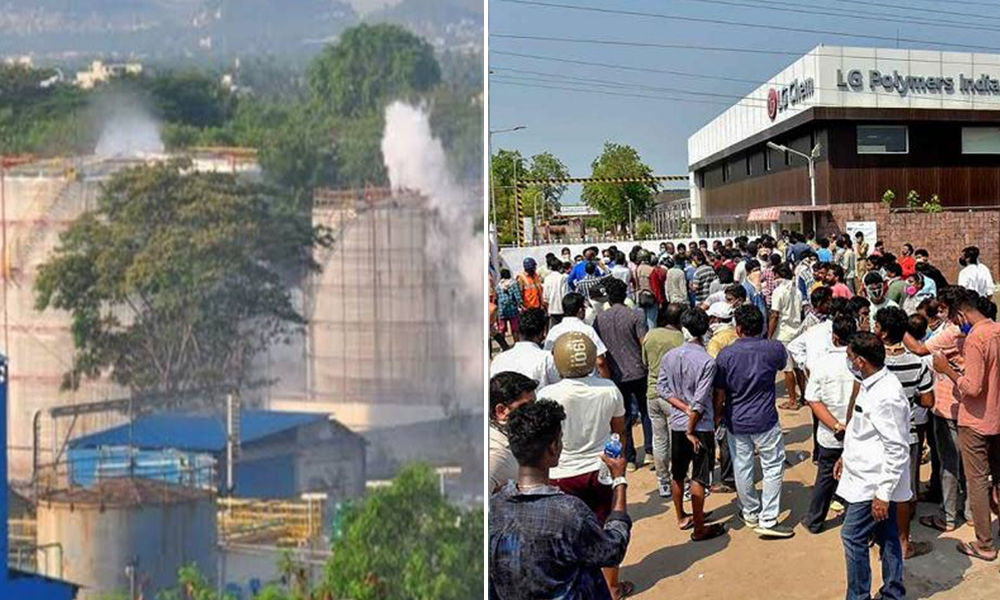

On May 7, a highly toxic styrene gas leaked from a chemical plant owned by the South Korean company LG Polymers India Pvt. Ltd in R. R. Venkatapuram village near Gopalapatnam on the outskirts of Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh.

The leakage caused widespread damage killing 11 people and hospitalizing approximately 100 people of whom at least 25 were reported to be serious. Besides this, more than 1000 persons were reported to be sick. The environment and habitat degradation were amongst various damages caused, including the fumes being spread over a radius of 3 to 4 kilometers.

The preliminary investigation highlights the negligence on the part of the authorities as one of the several factors for the accident. On the day of the leakage, the plant was re-opened following the nation-wide lockdown implemented as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The styrene gas which was supposed to be stored between 20-22 °C was left unattended since March 2020 due to the lockdown. The malfunctioning of the gas valve and a computer glitch in the factory’s cooling system allowed the temperatures to exceed the safe levels, thereby causing the gas to leak from the plant.

LEGAL ACTION

The National Green Tribunal took suo motu cognizance of the matter. The court observed that the Styrene gas is a hazardous chemical as defined under Rule 2(e) read with Entry 583 of Schedule I to the Manufacture, Storage and Import of Hazardous Chemical Rules, 1989. The Rules require on-site and off-site Emergency Plans to ensure the prevention of damage. There was apparent failure to comply with the said Rules and other statutory provisions as held by the Tribunal. Thus, the Tribunal invoked the principle of ‘Strict & Absolute Liability’ against the enterprise engaged in a hazardous or inherently dangerous industry.

Read Also: SC seeks reply from RBI and FM on waiver of interest on loans

The principal bench ordered compensation to the tune of 50 Crore to be deposited with the District Magistrate, Vishakhapatnam.

Strict Liability and Absolute Liability

The tortious principle of strict liability as laid down by the House of Lords in Rylands v. Fletcher holds the operator of the activity liable irrespective of him taking precautions to avoid the harm. It states that a person who brings on to his land anything likely to cause harm or injury is liable to pay damages when the thing escapes and causes harm. However, he is liable only when there is a non-natural use of land.

However, the rule has certain exceptions such as Act of God, default of the plaintiff, statutory authority, consent of the plaintiff and act of the third party.

Whereas the principle of Absolute liability has no exceptions that can be availed by the defendant. The principle was evolved by Justice P.N. Bhagwati in the case of M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (Oleum Gas leak Case) where the court observed that where an enterprise is engaged in a hazardous or inherently dangerous activity which poses a potential threat to the health and safety of the persons working in the factory and residing in surrounding areas, the industry owes an absolute and non-delegable duty to the community to ensure that no harm results to anyone on the account of the dangerous activity which it has undertaken. If harm is indeed caused, the enterprise is strictly and absolutely liable to compensate all those who are affected by the accident and such liability is not subject to any of the exceptions which operate under the principle of strict liability.

Read Also: Separate Bench of High Court to hear LG Polymers Gas leak case

SIMILAR EVENTS OF THE PAST

The incident made people hark back to the catastrophe of the Bhopal Gas Leak of 1984. It happened at a Union Carbide subsidiary pesticide plant in the city of Bhopal, India. Union Carbide India Limited was the Indian subsidiary of the American firm Union Carbide Corporation.

Immediately after the disaster where highly noxious methyl isocyanate (MIC) leaked from the UCIL plant, the parent company (UCC) began attempts to dissociate itself from responsibility for the gas leak. The principal tactic of UCC was to shift culpability to UCIL, stating the plant was wholly built and operated by the Indian subsidiary.

The Chairman and CEO of UCC, Warren Anderson was arrested and released on bail by the Madhya Pradesh Police in Bhopal. Anderson was taken to UCC’s house after which he was released six hours later on bail and flown out on a government plane. These actions were allegedly taken under the direction of then Chief Secretary of the state of MP, who was possibly instructed from the Chief Minister’s office, who himself flew out of Bhopal immediately.

Later in 1987, Anderson and other company executives were summoned by the Indian government, to appear in Indian court. In response, Union Carbide stated that the company is not under Indian jurisdiction.

After years of litigation, a settlement was eventually reached with the Indian Government through mediation which was accepted by the Supreme Court. The company agreed to pay $470 million in compensation, a relatively small amount of based on significant underestimations of the long-term health consequences of exposure and the number of people exposed.

Although, the gravity of the incident and the casualties were insurmountable, yet the administrative and legal system miserably failed in catering to the enormous problems such as that of rehabilitation, substantial relief and compensation for over several decades after the accident.

Since the disaster, India has experienced rapid industrialization. While some positive changes in government policy and behaviour of a few industries have taken place, major threats to the environment from poorly regulated industrial growth continues to remain. Widespread environmental degradation with significant adverse human health consequences continues to occur throughout the territory of India.

CONCLUSION

The inference which can be drawn from the matter is that it is difficult to fix the liability on the MNC’s involved even though there exists ample evidence of tortious negligence on their part.

But it is not only the international forums and foreign governments which are at fault, but the State itself which assists the MNC’s to escape the liability by diluting the charges or promoting economic progress at the cost of human health and life.

Moreover, in cases like these, the intricacies and technicalities in the law, generally result in the prosecution of subsidiaries in India while absolving the parent company from any sort of liability.

National governments and agencies on the international front should emphasize widely applicable techniques and methods for corporate responsibility and accident prevention as much in the developing world context as in advanced industrial nations of the world.

The pertinent question which now arises is that whether the Government and the Judiciary will step up to make the ends of justice meet.